Social movements don’t gain momentum automatically. People must be equipped for leadership and action. Too often this formative work is overshadowed by the headline-making events it makes possible. Women’s History Month provides an opportunity to shine a spotlight on women democracy educators whose everyday work helped shape and fuel transformative movements in American history—and eventually drive change right here in Minnesota.

Best known is social worker, domestic reformer, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Jane Addams. In 1889 Addams established Hull House in Chicago, an early American exemplar of the “settlement house”: a building in a poor urban neighborhood in which educated, middle-class women and men “settled” with the aim of better understanding social conditions, promoting reforms, and sharing knowledge and culture with their working-class, immigrant neighbors. Hull House became a vibrant neighborhood center in Chicago’s Near West Side, providing for the basic needs of local families as well as a space for learning and interaction across cultures. Addams took seriously the work of educating people for democratic citizenship, and Hull House offered an array of educational activities, all affirming the richness of participants’ diverse cultural traditions and their capacity to engage fruitfully with topics ranging from democracy and science to ethics and art.

Addams inspired community-based democracy educators in many different settings. One such educator was Septima Clark. In 1958, after years teaching school in South Carolina, Clark turned her talents toward establishing grassroots “citizenship schools” to incubate and scale the burgeoning civil rights movement. Clark, then at Highlander Folk School, led in conceiving and establishing these informal democracy education initiatives, which took place in beauty parlors, barber shops, church basements, and other places where people gathered to share time and stories. In these settings, disenfranchised black Americans developed not just literacy and numeracy, but familiarity with the power of nonviolent action, and confidence to carry on the freedom struggle.

In 1961, Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference assumed responsibility for the citizenship school movement, which subsequently mushroomed under the directorship of Dorothy Cotton. While the civil rights movement is remembered for marches and protests, the impact and even occurrence of such high-profile events depended on years of steady investment in everyday citizens’ capacity to make change. Citizenship schools, and the women who fueled their growth and work, were central to this tradition.

Minnesotans, too, have been central to the struggle for equal citizenship for all Americans. In 1924, Gertrude Brown, a black educator and social worker from North Carolina, came to Minneapolis to run the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House, the only local settlement house serving the black community. Under Brown, Phyllis Wheatley became a center for building “civic muscle” in the community, equipping its neighbors to tackle issues from housing discrimination to police brutality. Black students from the University of Minnesota, then barred from university dorms, were welcomed as residents and workers at Phyllis Wheatley, where Brown urged them to see themselves as citizens of the neighborhood, working with fellow citizens to steward and improve it. Several influential black leaders in the Twin Cities were shaped by this experience.

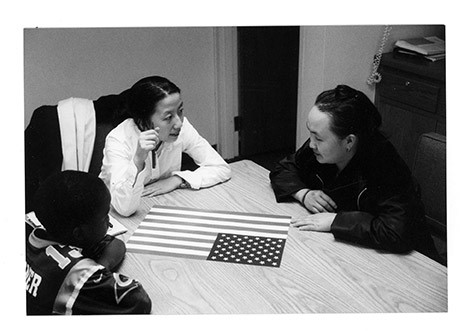

Decades later, two women democracy educators took up the mantle borne by Addams, Brown, Clark, and Cotton in an effort to revive the settlement-house and citizenship-school traditions here in Minnesota. In 1996, Nan Skelton (then at the University of Minnesota) and Nan Kari (at St. Paul’s College of St. Catherine, now St. Catherine University) led in establishing the Jane Addams School for Democracy (JAS). Initially based at Neighborhood House on the West Side of St Paul—one of the few remaining settlement houses in the Twin Cities—JAS integrated the community organizing experience of the citizenship schools with the theory of “public work” developed by Skelton’s then colleague at the U of M, Harry Boyte, who had recruited Cotton herself to help guide democracy education efforts he was developing through the university. Over the next two decades, thousands of East African, Latin American, and Southeast Asian immigrants found in JAS a “free space” in which their individual and collective talents were affirmed, developed, and directed toward the shaping of a democratic commonwealth in Minnesota.

Thank you for visiting the Minnesota Humanities Center blog.

Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog author and do not represent those of the Humanities Center, its staff, or any partner or affiliated organization, unless explicitly stated.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The owner of this blog makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this site or found by following any link on this site. Omissions, errors or mistakes are entirely unintentional.

The Humanities Center reserves the right to change, update or remove content on this blog at any time

By: Marie Ström

Marie Ström is Director of Education and Training at the Institute for Public Life and Work.